Monday 27 November 2023

- Thought Leadership

Softer commodity prices (including energy), base effects, a generally sluggish economy and a more restrictive monetary policy (interest rates rose from 0.1% in November 2021 to 5.25% in August 2023) all helped to arrest inflationary pressures. However, the Bank of England is still significantly overshooting its 2% inflation target.

Food price inflation is following and arguably driving this general trend. According to ONS figures, having peaked at a 45-year high of 19.2% in March 2023, by September it has eased to 12.2% . The biggest downward contributions in September came from dairy products (cheese prices have actually fallen in year on year terms) as well as mineral waters, soft drinks and juices.

While this improving trend is welcome, it is not the experience of the whole sector with prices for restaurant and café visits following a less steady trend. Having averaged increases of only 1.9% in 2019 (the last pre-Covid year) inflation in this part of the sector exploded between January 2022 and February 2023, from 4.3% to 11.4%.

Up until August 2023, the situation improved somewhat but the most recent data for September shows another increase (9.1%, up from 8.8% in August), the first deterioration since February 2023. Despite the generally improving trend in recent months, the ongoing cost of living crisis (which includes the rising costs for housing and energy) remains a key source of concern. In the October edition of “Opinions and Lifestyle Survey” conducted by the ONS, almost half of the respondents (48%) said they are buying less food due to the increasingly prohibitive cost.

Supply Chain Risk

As we work through the various indicators, the outlook becomes increasingly mixed. While consumer purchasing power is being dampened, supply chain risk in the sector has become less of a problem throughout 2023. Poor harvests in key agricultural markets as well as the war in Ukraine had caused the implementation of restrictions for customers purchasing fresh fruits or vegetables in late 2022 and early 2023. These bottlenecks have now disappeared, but the country is still dependent on large scale food imports.

There was further good news in August when the UK Government once again delayed the implementation of post-Brexit import rules for fresh farm produce for a fifth time, avoiding the higher costs associated with meeting additional requirements and increased border checks . With between 30-50% of the food consumed in the UK coming from abroad, this delay came as welcome relief to importers and domestic customers alike.

Labour Market

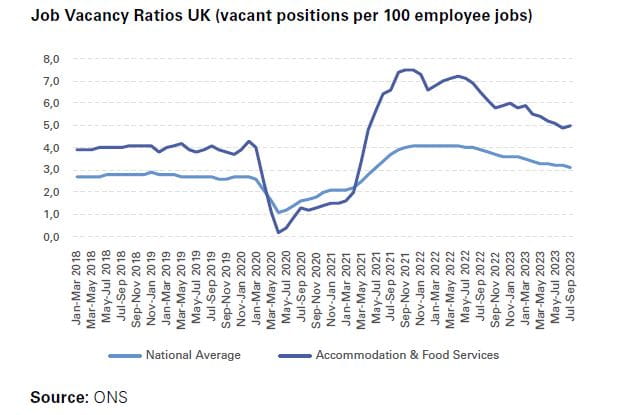

On the labour market front, the sector is experiencing two opposing trends. While on the one hand, labour shortages are less pressing than a year ago, wage costs have been rising steadily throughout 2023. Latest data from the ONS shows that by mid-2023 the number of open jobs in the UK had dropped below the 1m threshold for the first time since mid-2021 (and down from a peak of 1.3m in March to May 2022).

In the accommodation and food service sector, the number of vacant positions stood at 121,000 in Q3 2023, down from 159,000 a year earlier. Viewed as a ratio of vacant positions per 100 jobs in the sector, vacancies also reduced over recent quarters. In seasonally adjusted terms, the job vacancy ratio in the accommodation and food services sector has dropped from its peak of 7.5 in late 2021 to 5.0 in June to September 2023.

That said, this is still far above the most recent national average of 3.0 and it continues to be the highest ratio out of all 22 sectors monitored by the ONS. Whilst the data does seem to be moving in the right direction, it also suggests that wage inflation is likely to remain an issue in the sector in the short term.

Despite this gradual decrease in labour shortages, companies in the sector are facing increasingly higher wage costs. On a national level, annual pay growth (excluding bonuses) stood at 7.8% year on year for the period of June-August 2023, one of the highest levels recorded since the launch of the data series in 2001. Once bonuses are included, the figure rises to an even higher 8.1% but this is mainly driven by one-off payments made to public sector workers. As inflation remained on a downward trajectory and nominal wages rose quickly, real wages also continued to grow in mid-2023.

In June to August, total pay rose by 1.3% in real terms while regular pay (which excludes bonuses) increased by 1.1% compared to the same period last year.

In a sectoral comparison, the food sector has seen both above and below average pay rises during this period. On the production side of things, workers have seen relatively small pay increases (up by an average 4.8% on last year) while in the accommodation and food services sector, nominal wages increased by a much higher 8.1%. Retail trade (under which supermarkets fall) has seen wage growth of 7.7% in the June-August period and while higher wages will increase the available income to spend in retailers, they are also leading to lower profitability.

Return to Office

It is true to say that conditions within the sector have generally improved in 2023 but there are still obstacles to negotiate before we get to the point of full recovery. Footfall in inner cities has recovered after the complete lifting of Covid restrictions and several companies (including Amazon, BlackRock and JP Morgan) have implemented return to office policies for their employees. While office attendance ratios have risen in recent quarters, there are still a large number of employees who work from home, at least partially.

According to an ONS survey from May 2023, 39% of all workers have either worked fully or partially from home in the previous week and office vacancy rates in cities are still high. Even in London, rates are elevated, ranging from 8% in the West End to 10% in the City and 20% in Canary Wharf . Attendance rates have normalised somewhat during mid-week but are still low on Mondays and especially Fridays leaving shops and restaurants in inner cities having to deal with reduced demand.

2024 Outlook

Financial Performance

Overall, the sectoral outlook for the year ahead is more promising than it has been for some time. The cost of living crisis is gradually easing as inflation falls and real wages rise. Having said that, GfK’s Consumer Confidence Indicator deteriorated in October, reflecting growing pessimism in Britain’s households . After three months of improvement, the Index lost nine points, coming in at minus 30, the worst reading since July. But there is positivity to be found among food retailers.

The UK’s two largest are increasingly optimistic about the year ahead. Tesco, whose market share stands at around at 27% , recently upgraded its 2024 fiscal guidance to report retail adjusted operating profits of £2.6bn-2.7bn and retail free cash flow of between £1.8bn-2bn. This was an increase on the previous estimate of £1.4bn-1.8bn.

Sainsbury’s remain bullish with a market share of 14.8%. The supermarket group delivered 10.1% growth in retail sales for the first quarter of 2023, followed by 8.9% in the second. This performance has led Sainsbury’s to revise its profit predictions for the year by £30m to a minimum of £670m, with an upward ambition of delivering £700m.

Asda (13.7% market share) and Morrisons (8.6%, behind Aldi’s 9.9%) aren’t faring so well. Following takeovers that have increased both companies’ debt stock, Asda’s pre-tax profits for 2022 are down 80% with Morrisons experiencing a 50% drop in Q3 2023 profits. This performance was swiftly followed by the exit of the company’s CEO, CFO and COO.

Meanwhile, Lidl and Aldi continue to gain market share as the two discounters open new shops (and invest in new logistics infrastructure) and also attract cost-conscious shoppers. This trend is likely to persist in 2024 with Lidl (7.6% market share) projected to claim Morrisons’ number five spot in the not too distant future.

Credit Risk

So how do all of these mixed messages play out in terms of financial security in the sector? Worryingly, credit risk is likely to remain substantial in 2024, caused by poor economic growth and high interest rates. The Bank of England (BoE) did not increase interest rates in its latest meeting in early November but refinancing costs have risen sharply over the last two years - the BoE’s key policy rate has increased from 0.1% in November 2021 to 5.25% in just two years. While additional hikes are increasingly unlikely as inflation rates are coming down and the economy is switching into a lower gear, (the BoE believes there is a 50/50 chance of a recession in 2024), it is equally unlikely that monetary policy will be loosened in any meaningful way in 2024.

While the BoE might cut interest rates in the second half of next year, these measures would be limited in size and impact . Ongoing geopolitical tensions such as further escalation of the Israel-Gaza conflict and the ongoing war in Ukraine create additional headwinds that could dent confidence indicators and push inflation upwards once again. In that light, the price of oil is particularly concerning. While in November, the price was down 12% on the previous year, the price has risen from around US$75 per barrel of Brent to more than US$85 since July.

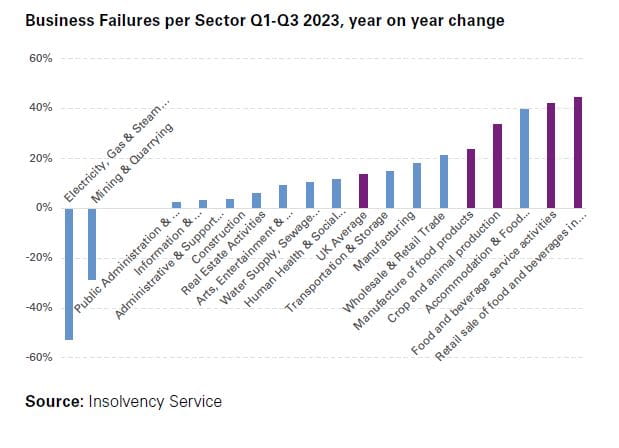

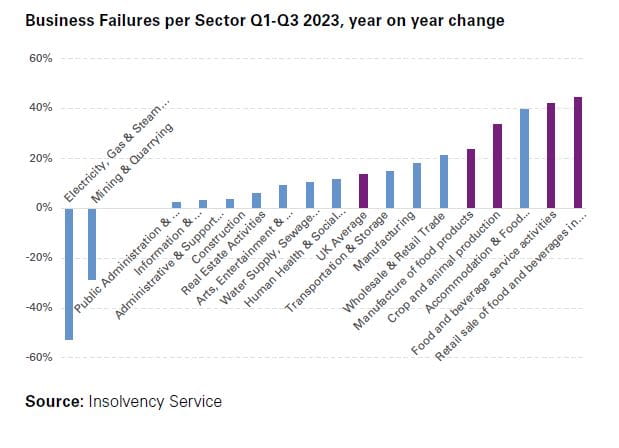

Of perhaps greatest concern is the news that business failures have already risen substantially in 2023 and the deteriorating trend continues to accelerate. In the food industry, data from the Government’s Insolvency Service shows that there have been 52 company insolvencies in crop and animal production between January and September, a 33% increase on last year.

Similar trends can be seen in other food-related sectors. The food manufacturing industry recorded 137 business failures in Q1-Q3 2023, compared with 111 in the same period last year, an increase of 23%. Meanwhile, retail sale of food, beverages and tobacco in specialised stores has seen a 44% increase (up to 208 business failures in the first three quarters of 2023). Following this trend is the food and beverage service sector - in Q1-Q3 2023, 2,545 companies filed for bankruptcy, compared with 1,790 in January-September 2022 (+42%). While the food-related sub-sectors of the economy only represent a small part of the overall business universe (18,367 business failures in Q1-Q3 2023), they all record above-average increases at the moment. For the UK as a whole, the number of business failures has increased by a sizable 14% in the first three quarters of 2023.